Before real water arrived via the rivers from the Andes, mirage lakes appeared in the Nazca Desert. The purpose of the canals was to tap into these lakes during dry spells, in the hope that this would trigger the arrival of real water along the dried-up arms of the rivers.

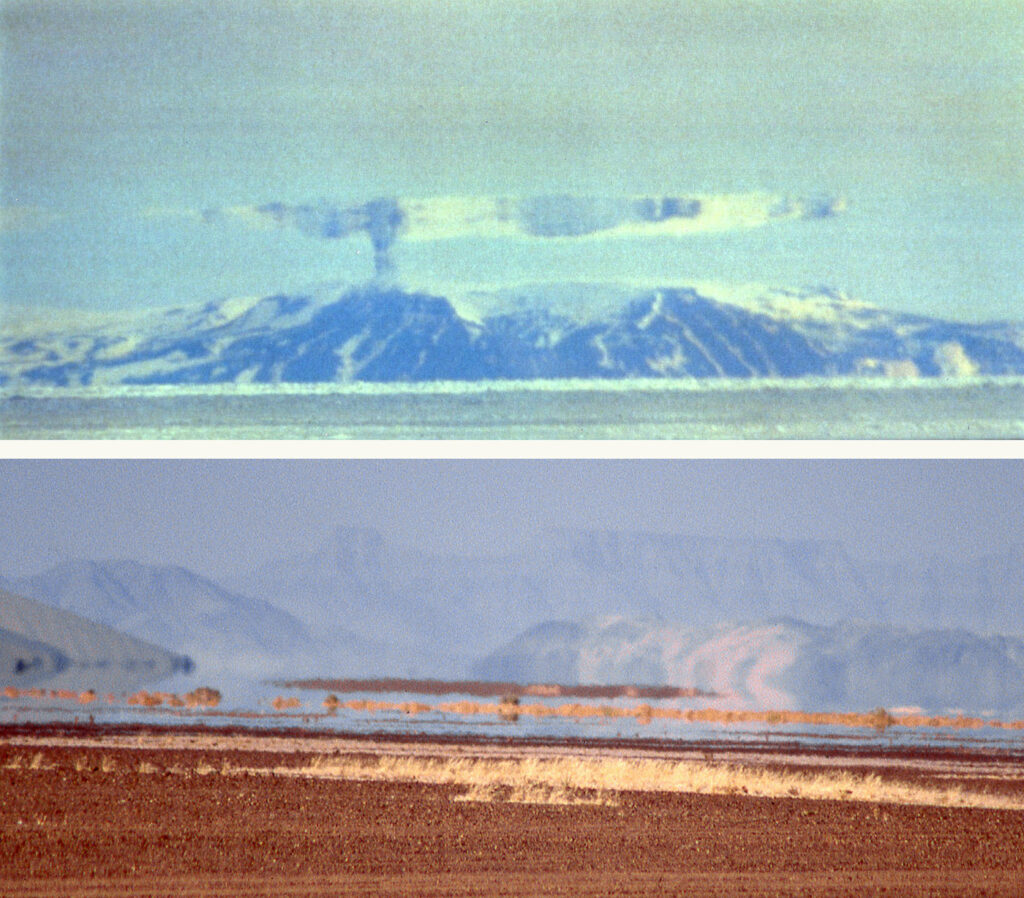

Just before Christmas 1980, coming from a work commitment in a copper mine in southern Peru, I travelled north through the Nazca Desert on a local bus. I asked the driver to drop me off at one of the long strips created by the Nazca civilisation. As I looked along it towards the horizon, I saw a huge lake, a mirage that had appeared there by chance. This phenomenon of a mirage in the desert is the well-known projection of the blue sky onto the ground, a mirage (lower image).

It occurs when you look across heated ground in a calm atmosphere and perceive light spreading in curved paths. If you look across a cool floor, you occasionally witness the opposite phenomenon: landscapes projected upside down in the sky (upper image). The mirage in the Nazca Desert occurred because the strong winds had stopped before Christmas due to the arrival of the El Niño current.

When I saw this illusion of water, I felt I understood what the people of Nazca intended with their huge channels in the dry desert: the absence of wind means rain for the Andes, as clouds can now move there. Within two weeks, the dried-up rivers actually bring fresh water.

I decided to study everything I could find about mirages and their relation to the human imagination. I soon realised that this single natural phenomenon, which had allowed early humans to see into another world, was to prove a rich source of inspiration for mythology and religion. At that time it could not be understood as an earthly optical phenomenon. Mirages did not find a scientific explanation until the 18th century. The influence of this very astonishing natural phenomenon of mirages on mythology and religion has been largely overlooked by anthropological research. Our ancestors were less concerned with pure fantasy than with natural science in their efforts to understand the environment and a possible other world.

The inverted world in the sky as a model for the otherworld has become deeply embedded in the subconscious of human beings. Three books (Books Das Rätsel der Götter: Fata Morgana, Die gläsernen Türme von Atlantis: Erinnerungen an Megalith-Europa, Als die Berge noch Flügel hatten: Die Fata Morgana in alten Kulturen, Mythen und Religionen) and two publications (Refs. 316, 447) followed. Characteristic of these encounters with mirages is the wide expanse of the view and the size of the objects sighted.

Large-scale monuments such as the Nazca lines, the pyramids and the megalithic arenas were used as observatories for mirages. They were used for communication with the otherworld and as instruments for weather forecasting (Book Ref. 4). The mythological and religious ideas of an inverted otherworld, of dragon-like mythical beings floating in the air, and of triple gods and triple worlds that have been handed down throughout the world are described in this book as ancient, naturalistic interpretations and idols of actually experienced superior mirages. The upper image shows mountains of Canada projected into the sky above a cool plain (provided by A. Takeno, Tokyo).

Deutsch

Deutsch Italiano

Italiano